Actuarial Standard of Practice No. 27

Selection of Economic Assumptions for Measuring Pension Obligations

STANDARD OF PRACTICE

TRANSMITTAL MEMORANDUM

September 2013

TO: Members of Actuarial Organizations Governed by the Standards of Practice of the Actuarial Standards Board and Other Persons Interested in the Selection of Economic Assumptions for Measuring Pension Obligations

FROM: Actuarial Standards Board (ASB)

SUBJ: Actuarial Standard of Practice (ASOP) No. 27

This document contains the final version of a revision of ASOP No. 27, Selection of Economic Assumptions for Measuring Pension Obligations.

Background

The ASB provides coordinated guidance for measuring pension and retiree group benefit obligations through the series of ASOPs listed below.

1. ASOP No. 4, Measuring Pension Obligations and Determining Pension Plan Costs or Contributions;

2. ASOP No. 6, Measuring Retiree Group Benefit Obligations;

3. ASOP No. 27, Selection of Economic Assumptions for Measuring Pension Obligations;

4. ASOP No. 35, Selection of Demographic and Other Noneconomic Assumptions for Measuring Pension Obligations; and

5. ASOP No. 44, Selection and Use of Asset Valuation Methods for Pension Valuations.

First Exposure Draft

The first exposure draft of this ASOP was issued in January 2011, with a comment deadline of April 30, 2011. Twenty comment letters were received and considered in developing modifications reflected in the second exposure draft.

Second Exposure Draft

The second exposure draft of this ASOP was issued in January 2012 with a comment deadline of May 31, 2012. The Pension Committee carefully considered the fifteen comment letters received. Changes made to the final standard in response to these comment letters include the following:

1. Section 3.5.1, Adverse Deviation or Other Valuation Issues, was revised to note that an actuary may determine that it is appropriate to adjust the economic assumptions when valuing plan provisions that are difficult to measure, as discussed in ASOP No. 4. Additionally, the title of this section was revised to Adverse Deviation or Plan Provisions That Are Difficult to Measure.

2. Section 3.6, Selecting a Reasonable Assumption, was revised to describe an economic assumption as reasonable if (among other criteria) it has no significant bias (the exposure draft used the word “unbiased”).

3. Section 4.1.1, Assumptions Used, was revised to require that each significant assumption be disclosed.

4. The first clause of the fourth paragraph of section 1.2, Scope, was removed because it contained guidance that was not useful.

5. Section 4.1.3, Changes in Assumptions, was revised to remove the word “nonprescribed” from the first sentence.

6. The language in Section 4.2 and Section 4.3 was revised to clarify how these sections dovetail with ASOP No. 41.

7. Section 4.4 was added to remove confusion regarding the interrelationship of this standard and Precept 9 of the Code of Professional Conduct.

8. Defined terms now appear in bold type. Bold type was exposed for comment with the second exposure draft of ASOP No. 4 and was well received.

In addition, a number of clarifying changes were made to the text. Please see Appendix 2 for a detailed discussion of the comments received and the reviewers’ responses.

Summary of Key Changes from the Previous Version of ASOP No. 27

The following are the four key changes from the previous version of ASOP No. 27 included in this version of ASOP No. 27:

1. This version clarifies that economic assumptions can be based either on the actuary’s estimate of future experience or on the actuary’s observations of the estimates inherent in market data, depending upon the purpose of the measurement.

2. The guidance regarding the reasonability of an economic assumption has been changed from the “best-estimate range” standard.

3. This version requires disclosing the rationale used in selecting each nonprescribed economic assumption or any changes made to nonprescribed economic assumptions.

4. The guidance now distinguishes between prescribed assumptions or methods set by law and prescribed assumptions or methods set by another party. The language in section 4.2 and section 4.3 was revised to incorporate this distinction and to clarify how these sections dovetail with ASOP No. 41.

ASOP No. 27 is intended to accommodate the concepts of financial economics as well as traditional actuarial practice.

The Pension Committee thanks everyone who took the time to contribute comments and suggestions on the exposure drafts.

The Pension Committee thanks former committee members Thomas B. Lowman, Tonya B. Manning, and Frank Todisco for their assistance with drafting this ASOP.

The ASB voted in September 2013 to adopt this standard.

Pension Committee of the ASB

Gordon C. Enderle, Chairperson

Mita D. Drazilov, Vice-Chairperson

C. David Gustafson Alan N. Parikh

Fiona E. Liston Mitchell I. Serota

A. Donald Morgan IV Judy K. Stromback

Christopher F. Noble Virginia C. Wentz

Actuarial Standards Board

Robert G. Meilander, Chairperson

Beth E. Fitzgerald Thomas D. Levy

Alan D. Ford Patricia E. Matson

Patrick J. Grannan James J. Murphy

Stephen G. Kellison James F. Verlautz

The ASB establishes and improves standards of actuarial practice. These ASOPs identify what the actuary should consider, document, and disclose when performing an actuarial assignment. The ASB’s goal is to set standards for appropriate practice for the U.S.

Section 1. Purpose, Scope, Cross References, and Effective Date

1.1 Purpose

This standard does the following:

a. provides guidance to actuaries in selecting (including giving advice on selecting) economic assumptions—primarily investment return, discount rate, post-retirement benefit increases, inflation, and compensation increases—for measuring obligations under defined benefit pension plans;

b. supplements the guidance in Actuarial Standard of Practice (ASOP) No. 4, Measuring Pension Obligations and Determining Pension Plan Costs or Contributions, that relate to the selection and use of economic assumptions; and

c. supplements the guidance in ASOP No. 6,Measuring Retiree Group Benefit Obligations, that relate to the selection and use of economic assumptions.

1.2 Scope

This standard applies to the selection of economic assumptions to measure obligations under any defined benefit pension plan that is not a social insurance program, as described in section 1.2, Scope, of ASOP No. 32, Social Insurance (unless ASOPs on social insurance explicitly call for application of this standard). Measurements of defined benefit pension plan obligations include calculations such as funding valuations or other assignment of plan costs to time periods, liability measurements or other actuarial present value calculations, and cash flow projections or other estimates of the magnitude of future plan obligations. Measurements of pension obligations do not generally include individual benefit calculations, individual benefit statement estimates, or nondiscrimination testing.

To the extent that the guidance in this standard may conflict with ASOP Nos. 4 or 6, ASOP Nos. 4 or 6 will govern. If a conflict exists between this standard and applicable law (statutes, regulations, and other legally binding authority), the actuary should comply with applicable law.

If the actuary departs from the guidance set forth in this standard in order to comply with applicable law or for any other reason the actuary deems appropriate, the actuary should refer to section 4.

The actuary should use the guidance set forth in this standard whenever the actuary has an obligation to assess the reasonableness of a prescribed assumption. The actuary’s obligations with respect to prescribed assumptions are governed by ASOP Nos. 4, 6, and 41, Actuarial Communications, which address prescribed assumptions and methods.

Throughout this standard, any reference to selecting economic assumptions also includes giving advice on selecting economic assumptions. For instance, the actuary may provide advice on selecting economic assumptions under US GAAP or Governmental Accounting Standards even though another party is ultimately responsible for selecting these assumptions. This standard applies to the actuarial advice given in such situations, within the constraints imposed by the relevant accounting standards.

1.3 Cross References

When this standard refers to the provisions of other documents, the reference includes the referenced documents as they may be amended or restated in the future, and any successor to them, by whatever name called. If any amended or restated document differs materially from the originally referenced document, the actuary should consider the guidance in this standard to the extent it is applicable and appropriate.

1.4 Effective Date

This standard will be effective for any actuarial work product with a measurement date on or after September 30, 2014.

Section 2. Definitions

The terms below are defined for use in this actuarial standard of practice.

2.1 Inflation

General economic inflation, defined as price changes over the whole of the economy.

2.2 Measurement Date

The date as of which the value of the pension obligation is determined (sometimes referred to as the “valuation date”).

2.3 Measurement Period

The period subsequent to the measurement date during which a particular economic assumption will apply in a given measurement.

2.4 Merit Adjustments

The rates of change in an individual’s compensation attributable to personal performance, promotion, seniority, or other individual factors.

2.5 Prescribed Assumption or Method Set by Another Party

A specific assumption or method that is selected by another party, to the extent that law, regulation, or accounting standards gives the other party responsibility for selecting such an assumption or method. For this purpose, an assumption or method selected by a governmental entity for a plan that such governmental entity or a political subdivision of that entity directly or indirectly sponsors is a prescribed assumption or method set by another party.

2.6 Prescribed Assumption or Method Set by Law

A specific assumption or method that is mandated or that is selected from a specified range or set of assumptions or methods that is deemed to be acceptable by applicable law (statutes, regulations, and other legally binding authority). For this purpose, an assumption or method selected by a governmental entity for a plan that such governmental entity or a political subdivision of that entity directly or indirectly sponsors is not a prescribed assumption or method set by law.

2.7 Productivity Growth

The rates of change in a group’s compensation attributable to the change in the real value of goods or services per unit of work.

Section 3. Analysis of Issues and Recommended Practices

3.1 Overview

Pension obligation values incorporate assumptions about pension payment commencement, duration, and amount. They also require discount rates to convert future expected payments into present values. Some of these assumptions are economic assumptions covered under ASOP No. 27 and some are noneconomic assumptions covered under ASOP No. 35, Selection of Demographic and Other Noneconomic Assumptions for Measuring Pension Obligations. In order to measure a pension obligation, the actuary will need to select or evaluate assumptions underlying the obligation.

3.2 Identification of Economic Assumptions Used in the Measurement

The actuary should consider the following factors when identifying the types of economic assumptions to use for a specific measurement:

a. the purpose of the measurement;

b. the characteristics of the obligation to be measured (measurement period, pattern of plan payments over time, open/closed group, materiality, volatility, etc.); and

c. materiality of the assumption to the measurement (see section 3.5.2).

The types of economic assumptions used to measure obligations under a defined benefit pension plan may include inflation, investment return, discount rate, compensation increases, and other economic factors such as Social Security, cost-of-living adjustments, rate of payroll growth, growth of individual account balances, and variable conversion factors.

3.3 General Selection Process

After identifying the economic assumptions to be used for the measurement, the actuary should follow the general process set forth below for selecting each economic assumption for a specific measurement:

a. identify components, if any, of the assumption;

b. evaluate relevant data (section 3.4);

c. consider factors specific to the measurement;

d. consider other general factors (section 3.5); and

e. select a reasonable assumption (section 3.6).

After completing these steps for each economic assumption, the actuary should review the set of economic assumptions for consistency (section 3.12) and make appropriate adjustments if necessary.

3.4 Relevant Data

To evaluate relevant data, the actuary should review appropriate recent and long-term historical economic data. The actuary should not give undue weight to recent experience. The actuary should consider the possibility that some historical economic data may not be appropriate for use in developing assumptions for future periods due to changes in the underlying environment. Appendix 4 lists some generally available sources of economic data and analyses.

3.5 Other General Considerations

The following issues should be addressed when applicable:

3.5.1 Adverse Deviation or Plan Provisions That Are Difficult to Measure

Depending on the purpose of the measurement, the actuary may determine that it is appropriate to adjust the economic assumptions to provide for considerations such as adverse deviation or plan provisions that are difficult to measure, as discussed in ASOP No. 4. Any such adjustment made should be disclosed in accordance with section 4.1.1.

3.5.2 Materiality

The actuary should consider the balance between refined economic assumptions and materiality. The actuary is not required to use a particular type of economic assumption or to select a more refined economic assumption when in the actuary’s professional judgment such use or selection is not expected to produce materially different results.

3.5.3 Cost of Using Refined Assumptions

The actuary should consider the balance between refined economic assumptions and the cost of using refined assumptions. For example, actuaries working with small plans may prefer to emphasize the results of general research to comply with this standard. However, they are not precluded from using relevant plan-specific facts.

3.5.4 Rounding

Taking into account the purpose of the measurement, materiality, and the cost of using refined assumptions, the actuary may determine that it is appropriate to apply a rounding technique to the selected economic assumption. In such cases, the rounding technique should be unbiased.

3.5.5 Changes in Circumstances

The economic assumptions selected should reflect the actuary’s knowledge as of the measurement date. However, the actuary may learn of an event occurring after the measurement date that would have changed the actuary’s selection of an economic assumption. (For example, a collective bargaining agreement ratified after the measurement date may lead the actuary to change the compensation increase assumption that otherwise would have been selected.) If appropriate, the actuary may reflect this change as of the measurement date.

3.5.6 Views of Experts

Economic data and analyses are available from a variety of sources, including representatives of the plan sponsor and administrator, investment advisors, economists, and other professionals. When the actuary is responsible for selecting or giving advice on selecting economic assumptions within the scope of this standard, the actuary may incorporate the views of experts but the selection or advice should reflect the actuary’s professional judgment.

3.6 Selecting a Reasonable Assumption

Each economic assumption selected by the actuary should be reasonable. For this purpose, an assumption is reasonable if it has the following characteristics:

a. It is appropriate for the purpose of the measurement;

b. It reflects the actuary’s professional judgment;

c. It takes into account historical and current economic data that is relevant as of the measurement date;

d. It reflects the actuary’s estimate of future experience, the actuary’s observation of the estimates inherent in market data, or a combination thereof; and

e. It has no significant bias (i.e., it is not significantly optimistic or pessimistic), except when provisions for adverse deviation or plan provisions that are difficult to measure are included and disclosed under section 3.5.1, or when alternative assumptions are used for the assessment of risk.

3.6.1 Reasonable Assumption Based on Future Experience or Market Data

The actuary should develop a reasonable economic assumption based on the actuary’s estimate of future experience, the actuary’s observation of the estimates inherent in market data, or a combination thereof. Examples of how the actuary may observe estimates inherent in market data include the following:

a. comparing yields on inflation-indexed bonds to yields on equivalent non-inflation-indexed bonds as a part of estimating the market’s expectation of future inflation;

b. comparing yields on bonds of different credit quality to determine market credit spreads;

c. observing yields on U.S. Treasury debt of various maturities to determine a yield curve free of credit risk; and

d. examining annuity prices to estimate the market price to settle pension obligations.

The items listed above, as well as other market observations or prices, include estimates of future experience as well as other considerations. For example, the difference in yields between inflation-linked and non- inflation-linked bonds may include premiums for liquidity and future inflation risk in addition to an estimate of future inflation. The actuary may want to adjust estimates based on observations to reflect the various risk premiums and other factors (such as supply and demand for tradable bond or debt securities) that might be reflected in market pricing.

3.6.2 Range of Reasonable Assumptions

The actuary should recognize the uncertain nature of the items for which assumptions are selected and, as a result, may consider several different assumptions reasonable for a given measurement. The actuary should also recognize that different actuaries will apply different professional judgment and may choose different reasonable assumptions. As a result, a range of reasonable assumptions may develop both for an individual actuary and across actuarial practice.

3.7 Selecting an Inflation Assumption

If the actuary is using an approach that treats inflation as an explicit component of other economic assumptions or as an independent assumption, the actuary should follow the general process set forth in section 3.3 to select an inflation assumption.

3.7.1 Data

The actuary should review appropriate inflation data. These data may include consumer price indices, the implicit price deflator, forecasts of inflation, yields on government securities of various maturities, and yields on nominal and inflation-indexed debt.

3.7.2 Select and Ultimate Inflation Rates

The actuary may assume select and ultimate inflation rates in lieu of a single inflation rate. Select and ultimate inflation rates vary by period from the measurement date (for example, inflation of 3% for the first 5 years following the measurement date and 4% thereafter).

3.8 Selecting an Investment Return Assumption

The investment return assumption reflects the anticipated returns on the plan’s current and, if appropriate for the measurement, future assets. This assumption is typically constructed by considering various factors including, but not limited to, the time value of money; inflation and inflation risk; illiquidity; credit risk; macroeconomic conditions; and growth in earnings, dividends, and rents.

In developing a reasonable assumption for these factors and in combining the factors to develop the investment return assumption, the actuary may consider a broad range of data and other inputs, including the judgment of investment professionals.

3.8.1 Data

The actuary should review appropriate investment data. These data may include the following:

a. current yields to maturity of fixed income securities such as government securities and corporate bonds;

b. forecasts of inflation, GDP growth, and total returns for each asset class;

c. historical and current investment data including, but not limited to, real and nominal returns, the inflation and inflation risk components implicit in the yield of inflation-protected securities, dividend yields, earnings yields, and real estate capitalization rates; and

d. historical plan performance.

The actuary may also consider historical and current statistical data showing standard deviations, correlations, and other statistical measures related to historical or future expected returns of each asset class and to inflation. Stochastic simulation models or other analyses may be used to develop expected investment returns from this statistical data.

3.8.2 Components of the Investment Return Assumption

The investment return assumption can be developed using various methods consistent with the guidance set forth in this standard, including combining estimated components of the assumption. Where the assumption is determined as the result of a combination of two or more components or factors, the actuary should ensure that the combination of these factors is logically consistent.

3.8.3 Measurement-Specific Considerations

The actuary should address factors specific to each measurement in selecting an investment return assumption. Examples of such factors are as follows:

a. Investment Policy-The plan’s investment policy may include the following: (i) the current allocation of the plan’s assets; (ii) types of securities eligible to be held (diversification, marketability, social investing philosophy, etc.); (iii) a stationary or dynamic target allocation of plan assets among different classes of securities; and (iv) permissible ranges for each asset class within which the investment manager is authorized to make investment decisions. The actuary should consider whether the current investment policy is expected to change during the measurement period.

b. Effect of Reinvestment-Two reinvestment risks are associated with traditional, fixed income securities: (i) reinvestment of interest and normal maturity values not immediately required to pay plan benefits, and (ii) reinvestment of the entire proceeds of a security that has been called by the issuer.

c. Investment Volatility-Plans investing heavily in those asset classes characterized by high variability of returns may be required to liquidate those assets at depressed values to meet benefit obligations. Other investment risks may also be present, such as default risk or the risk of bankruptcy of the issuer.

d. Investment Manager Performance-Anticipating superior (or inferior) investment manager performance may be unduly optimistic (or pessimistic). The actuary should not assume that superior or inferior returns will be achieved, net of investment expenses, from an active investment management strategy compared to a passive investment management strategy unless the actuary believes, based on relevant supporting data, that such superior or inferior returns represent a reasonable expectation over the measurement period.

e. Investment and Other Administrative Expenses-Investment and other administrative expenses may be paid from plan assets. To the extent such expenses are not otherwise recognized, the actuary should reduce the investment return assumption to reflect these expenses.

f. Cash Flow Timing-The timing of expected contributions and benefit payments may affect the plan’s liquidity needs and investment opportunities.

g. Benefit Volatility-Benefit volatility may be a primary factor for small plans with unpredictable benefit payment patterns. It may also be an important factor for a plan of any size that provides highly subsidized early-retirement benefits, lump-sum benefits, or supplemental benefits triggered by corporate restructuring or financial distress. In such plans, the untimely liquidation of securities at depressed values may be required to meet benefit obligations.

h. Expected Plan Termination-In some situations, the actuary may expect the plan to be terminated at a determinable date. For example, the actuary may expect a plan to terminate when the owner retires, or a frozen plan to terminate when assets are sufficient to provide all accumulated plan benefits. In these situations, the investment return assumption may reflect a shortened measurement period that ends at the expected termination date.

i. Tax Status of the Funding Vehicle-If the plan’s assets are not kept in a tax-exempt fund, income taxes may reduce the plan’s investment return. Taxes may be reflected by an explicit reduction in the total investment return assumption or by a separately identified assumption.

j. Arithmetic and Geometric Returns-The use of a forward looking expected arithmetic return as an investment return assumption will produce a mean accumulated value. The use of a forward looking expected geometric return as an investment return assumption will produce an accumulated value that generally converges to the median accumulated value as the time horizon lengthens. The actuary should consider the implications of a forward looking expected arithmetic return and a forward looking expected geometric return when constructing an investment return assumption.

In some instances, the actuary will collect forward looking expected returns by asset class from external sources. The actuary should take appropriate steps to determine the time horizon, the price inflation, and the expenses reflected in the expected returns. In addition, the actuary should take steps to determine the type of forward looking expected returns collected from external sources (i.e., forward looking expected geometric returns or forward looking expected arithmetic returns) and that they are used appropriately. For example, when determining a forward looking expected geometric return for an entire portfolio, the actuary generally should not take the weighted average of the forward looking expected geometric return for each of the asset classes. In this instance, to determine the forward looking expected geometric return for an entire portfolio, the actuary should take the weighted average of the forward looking expected arithmetic return for each of the asset classes and adjust such determination to reflect the variance of the entire portfolio.

Appendix 3 includes general background on arithmetic and geometric returns.

3.8.4 Multiple Investment Return Rates

The actuary may assume multiple investment return rates in lieu of a single investment return rate. Two examples are as follows:

a. Select and Ultimate Investment Return Rates-Assumed investment return rates vary by period from the measurement date (for example, returns of 8% for the first 10 years following the measurement date and 6% thereafter). When assuming select and ultimate investment return rates, the actuary should consider the relationships among inflation, interest rates, and market appreciation (depreciation).

b. Benefit Payments Covered by Designated Current or Projected Assets-One investment return rate is assumed for benefit payments covered by designated current or projected plan assets on the measurement date, and a different investment return rate is assumed for the balance of the benefit payments and assets.

3.9 Selecting a Discount Rate

A discount rate is used to calculate the present value of expected future plan payments. A discount rate may be a single rate or a series of rates, such as a yield curve. The actuary should consider the purpose of the measurement as a primary factor in selecting a discount rate. Some examples of measurement purposes are as follows:

a. Contribution Budgeting-An actuary evaluating the sufficiency of a plan’s contribution policy may choose among several discount rates. The actuary may use a discount rate that reflects the anticipated investment return from the pension fund. Alternatively, the actuary may use a discount rate appropriate for defeasance, settlement, or market-consistent measurements.

b. Defeasance or Settlement-An actuary measuring a plan’s present value of benefits on a defeasance or settlement basis may use a discount rate implicit in annuity prices or other defeasance or settlement options.

c. Market-Consistent Measurements-An actuary making a market-consistent measurement may use a discount rate implicit in the price at which benefits that are expected to be paid in the future would trade in an open market between a knowledgeable seller and a knowledgeable buyer. In some instances, that discount rate may be approximated by market yields for a hypothetical bond portfolio whose cash flows reasonably match the pattern of benefits expected to be paid in the future. The type and quality of bonds in the hypothetical portfolio may depend on the particular type of market-consistent measurement.

The present value of expected future pension payments may be calculated from the perspective of different parties, recognizing that different parties may have different measurement purposes. For example, the present value of expected future payments could be calculated from the perspective of an outside creditor or the entity responsible for funding the plan. The outside creditor may desire a discount rate consistent with other measurements of importance to the creditor even though those other measurements may have little or no importance to the entity funding the plan.

3.10 Selecting a Compensation Increase Assumption

Compensation is a factor in determining participants’ benefits in many pension plans. Also, some actuarial cost methods take into account the present value of future compensation. Generally, a participant’s compensation will increase over the long term in accordance with inflation, productivity growth, and merit adjustments. The assumption used to measure the anticipated year-to-year change in compensation is referred to as the compensation increase assumption. It may be a single rate, it may vary by age or service, or it may vary over future years.

When selecting a compensation increase assumption, the actuary should address the following factors:

3.10.1 Data

The actuary should review available compensation data. These data may include the following:

a. the plan sponsor’s current compensation practice and any anticipated changes in this practice;

b. current compensation distributions by age or service;

c. historical compensation increases and practices of the plan sponsor and other plan sponsors in the same industry or geographic area; and

d. historical national wage increases and productivity growth.

The actuary should consider available plan-sponsor-specific compensation data, but the actuary should carefully weigh the credibility of these data when selecting the compensation increase assumption. For small plans or recently formed plan sponsors, industry or national data may provide a more appropriate basis for developing the compensation increase assumption.

3.10.2 Measurement-Specific Considerations

The actuary should consider factors specific to each measurement in selecting a specific compensation increase assumption. Examples of such factors are as follows:

a. Compensation Practice-The plan sponsor’s current compensation practice and any contemplated changes may affect the compensation increase assumption, at least in the short term. For example, if pension benefits are a function of base compensation and the plan sponsor is changing its compensation practice to put greater emphasis on incentive compensation, future growth in base compensation may differ from historical patterns.

b. Competitive Factors-The level and pattern of future compensation changes may be affected by competitive factors, including competition for employees both within the plan sponsor’s industry and within the geographical areas in which the plan sponsor operates, and global price competition. Unless the measurement period is short, the actuary should not give undue weight to short-term patterns.

c. Collective Bargaining-The collective bargaining process impacts the level and pattern of compensation changes. However, it may not be appropriate to assume that future contracts will provide the same level of compensation changes as the current or recent contracts.

d. Compensation Volatility-If certain elements of compensation, such as bonuses and overtime, tend to vary materially from year to year, or if aberrations exist in recent compensation amounts, then volatility should be taken into account. In some circumstances, this may be accomplished by adjusting the base amount from which future compensation elements are projected (for example, the projected bonuses might be based on an adjusted average of bonuses over the last 3 years). In some other circumstances, an additional assumption regarding an expected increase in pay in the final year of service may be used.

e. Expected Plan Freeze or Termination-In some situations, as stated in section 3.8.3(h), the actuary may expect the plan to be frozen or terminated at a determinable date. In these situations, the compensation increase assumption may reflect a shortened measurement period that ends at the expected termination date.

3.10.3 Multiple Compensation Increase Assumptions

The actuary may use multiple compensation increase assumptions in lieu of a single compensation increase assumption. Three examples are as follows:

a. Select and Ultimate Assumptions-Assumed compensation increases vary by period from the measurement date (for example, 4% increases for the first 5 years following the measurement date, and 5% thereafter) or by age or service.

b. Separate Assumptions for Different Employee Groups-Different compensation increases are assumed for two or more employee groups that are expected to receive different levels or patterns of compensation increases.

c. Separate Assumptions for Different Compensation Elements-Different compensation increases are assumed for two or more compensation elements that are expected to change at different rates (for example, 5% bonus increases and 3% increases in other compensation elements).

3.11 Selecting Other Economic Assumptions

In addition to inflation, investment return, discount rate, and compensation increase assumptions, the following are some of the types of economic assumptions that may be required for measuring certain pension obligations. The actuary should follow the general process described in section 3.3 to select these assumptions. The selected assumptions should also satisfy the consistency requirement of section 3.12.

Social Security benefits are based on an individual’s covered earnings, the OASDI contribution and benefit base, and changes in the cost of living. Changes in the OASDI contribution and benefit base are determined from changes in national average wages, which reflect the change in national productivity and inflation.

3.11.2 Cost-of-Living Adjustments

Plan benefits or limits affecting plan benefits (including the Internal Revenue Code (IRC) section 401(a) (17) compensation limit and section 415(b)(maximum annuity) may be automatically adjusted for inflation or assumed to be adjusted for inflation in some manner (for example, through regular plan amendments). However, for some purposes (such as qualified pension plan funding valuations), the actuary may be precluded by applicable laws or regulations from anticipating future plan amendments or future cost-of-living adjustments in certain IRC limits.

3.11.3 Rate of Payroll Growth

As a result of terminations and new participants, total payroll generally grows at a different rate than does a participant’s salary or the average of all current participants combined. As such, when a payroll growth assumption is needed, the actuary should use an assumption that is consistent with but typically not identical to the compensation increase assumption. One approach to setting the payroll growth assumption may be to reduce the compensation increase assumption by the effect of any assumed merit increases. The actuary should apply professional judgment in determining whether, given the purpose of the measurement, the payroll growth assumption should be based on a closed or open group and, if the latter, whether the size of that group should be expected to increase, decrease, or remain constant.

3.11.4 Growth of Individual Account Balances

Certain plan benefits have components directly related to the accumulation of real or hypothetical individual account balances (for example, so-called floor-offset arrangements and cash balance plans). See ASOP No. 4 for further guidance regarding these types of benefits.

3.11.5 Variable Conversion Factors

Measuring certain pension plan obligations may require converting from one payment form to another, such as converting a projected individual account balance to an annuity, converting an annuity to a lump sum, or converting from one annuity form to a different annuity form. The conversion factors may be variable (for example, recalculated each year based on a stated mortality table and interest rate equal to the yield on 30-year Treasury bonds).

3.12 Consistency among Economic Assumptions Selected by the Actuary for a Particular Measurement

With respect to any particular measurement, each economic assumption selected by the actuary should be consistent with every other economic assumption selected by the actuary for the measurement period, unless the assumption, considered individually, is not material, as provided in section 3.5.2. A number of factors may interact with one another and may be components of other economic assumptions, such as inflation, economic growth, and risk premiums. In some circumstances, consistency may be achieved by using the same inflation, economic growth, and other relevant components in each of the economic assumptions selected by the actuary.

Consistency is not necessarily achieved by maintaining a constant difference between one economic assumption and another. For each measurement date, the actuary should reevaluate the individual assumptions and the relationships among them, and make appropriate adjustments.

Assumptions selected by the actuary need not be consistent with prescribed assumptions, which are discussed in section 3.13.

3.13 Prescribed Assumption(s)

The actuary should use the guidance set forth in this standard whenever the actuary has an obligation to assess the reasonableness of a prescribed assumption. The actuary’s obligations with respect to prescribed assumptions are governed by section 4.2 of this ASOP and by ASOP Nos. 4, 6, or 41 as applicable, which address prescribed assumptions and methods.

Section 4. Communications and Disclosures

4.1 Communications

Any actuarial report prepared to communicate the results of work subject to this standard should contain the following disclosures with respect to economic assumptions:

4.1.1 Assumptions Used

The actuary should describe each significant assumption used in the measurement and whether the assumption represents an estimate of future experience, the actuary’s observation of the estimates inherent in market data, or a combination thereof. Sufficient detail should be shown to permit another qualified actuary to assess the level and pattern of each assumption.

Depending on a particular measurement’s circumstances, the actuary may give information about specific interrelationships among the assumptions (for example, investment return: 8% per year, net of investment expenses and including inflation at 3%). The description should also include a disclosure of any explicit adjustment made in accordance with section 3.5.1 for adverse deviation or plan provisions that are difficult to measure as discussed in ASOP No. 4.

4.1.2 Rationale for Assumptions

The actuary should disclose the information and analysis used in selecting each economic assumption that has a significant effect on the measurement. The disclosure may be brief but should be pertinent to the plan’s circumstances. For example, the actuary may disclose any specific approaches used, sources of external advice, and how past experience and future expectations were considered. The disclosure may reference any actuarial experience report or study performed, including the date of the report or study. This section is not applicable to prescribed assumptions or methods set by another party nor is it applicable to prescribed assumptions or methods set by law.

4.1.3 Changes in Assumptions

The actuary should disclose any changes in the economic assumptions from those previously used for the same type of measurement. The general effects of the changes should be disclosed in words or by numerical data, as appropriate. For assumptions that were not prescribed, the actuary should include an explanation of the information and analysis that led to the changes.

The disclosure may be brief but should be pertinent to the plan’s circumstances. The disclosure may reference any actuarial experience report or study performed, including the date of the report or study.

4.1.4 Changes in Circumstances

The actuary should refer to ASOP No. 41 for communication and disclosure requirements regarding changes in circumstances known to the actuary that occur after the measurement date and that would affect economic assumptions selected as of the measurement date.

4.2 Disclosure about Prescribed Assumptions or Methods

The actuary’s communication should state the source of any prescribed assumptions or methods.

With respect to prescribed assumptions or methods set by another party, the actuary’s communication should identify the following, if applicable:

1. any prescribed assumption or method set by another party that significantly conflicts with what, in the actuary’s professional judgment, would be reasonable for the purpose of the measurement (section 3.13); or

2. any prescribed assumption or method set by another party that the actuary is unable to evaluate for reasonableness for the purpose of the measurement (section 3.13).

4.3 Additional Disclosures

The actuary should also include the following, as applicable, in an actuarial communication:

1. the disclosure in ASOP No. 41, section 4.3, if the actuary states reliance on other sources and thereby disclaims responsibility for any material assumption or method set by a party other than the actuary; and

2. the disclosure in ASOP No. 41, section 4.4, if, in the actuary’s professional judgment, the actuary has otherwise deviated materially from the guidance of this ASOP.

4.4 Confidential Information

Nothing in this standard is intended to require the actuary to disclose confidential information.

Appendix 1 – Background and Current Practices

Note: This appendix is provided for informational purposes but is not part of the standard of practice.

Background

Economic assumptions have a significant effect on any pension obligation measurement. Small changes of 25 or 50 basis points in these assumptions can change the measurement by several percentage points or more. Assumptions such as compensation increases or cash balance crediting rates are often used to determine projected benefit streams for valuation purposes. The discount rate assumption, arguably the most critical economic assumption in determining a pension obligation, is used to determine the discounted present value of all benefit streams that are part of such obligation measurement.

Historically, actuaries have used various practices for selecting economic assumptions. For example, some actuaries have looked to surveys of economic assumptions used by other actuaries, some have relied on detailed research by experts, some have used highly sophisticated projection techniques, and many actuaries have used a combination of these.

The first decade of the 21st century contained a significant amount of debate inside and outside the actuarial profession regarding the measurement of pension obligations. Much of the debate centered on the economic assumptions actuaries use to measure these obligations. The decade also saw the emergence of a financial economic viewpoint on pension obligations. Applying financial economic theory to the measurement of pension obligations has been controversial and has produced a significant amount of debate in the actuarial profession.

Current Practices

The actuary’s discretion over economic assumptions has been curtailed in many situations. In the private single employer plan arena, the IRS, PBGC, and FASB have promulgated rulings that have limited or effectively removed an actuary’s judgment regarding the discount rate used for current-year funding or accounting. Actuaries can still set other economic assumptions, such as compensation increases, inflation, or fixed income yields.

For plans other than private single-employer plans (for example, church plans, multi-employer plans, public plans), the discount rate for current-year funding requirements may or may not be prescribed by other entities. Funding valuations for these types of plans often use a discount rate related to the expected return on plan assets. In practice, this discount rate (return on asset) assumption may be set by the legislative body, plan sponsor, a governing board of trustees, or the actuary. The actuary may advise the plan sponsor about the selection of the discount rate.

As in the single-employer situation, the actuary may have discretion over other economic assumptions used to measure obligations for plans other than private single-employer plans. Alternatively, the actuary may be in an advisory position, helping the legislative body, plan sponsor, or governing board of trustees select the assumptions.

The focus on solvency in the private single-employer plan arena has come along with prescribed economic assumptions that are linked to capital market indices. Actuaries practicing in this area are becoming accustomed to changing assumptions frequently. In nonprescribed situations, practice is still dependent upon the individual actuary. Many actuaries change assumptions infrequently, while other actuaries reevaluate the assumptions as of each measurement date and change economic assumptions more frequently. In the public plan arena, many entities perform assumption reviews every few years, and these reviews may or may not lead to assumption adjustments.

In preparing calculations for purposes other than current-year plan valuations, actuaries often use economic assumptions that are different from those used for the current-year valuation.

Appendix 2 – Comments on the Second Exposure Draft and Responses

The second exposure draft of this proposed revision of this ASOP, Selection of Economic Assumptions for Measuring Pension Obligations, was issued in January 2012 with a comment deadline of May 31, 2012. Fifteen comment letters were received. Some of the letters were submitted on behalf of multiple commentators, such as by firms or committees. For purposes of this appendix, the term “commentator” may refer to more than one person associated with a particular comment letter. The Pension Committee carefully considered all comments received, and the ASB reviewed (and modified, where appropriate) the proposed changes.

Click here to view Appendix 2 in its entirety.

Appendix 3 – Arithmetic and Geometric Returns

A. INTRODUCTION

One of the most important assumptions an actuary uses in measuring pension obligations is the discount rate.The exposure draft of ASOP No. 27 issued in January 2011 included the following question intransmittal memorandum:

“4. Do you agree that the guidance on arithmetic and geometric returns is appropriate? Should the consequences of the use of geometric or arithmetic returns be disclosed?”

Given the wide range of responses received to the above question, the Pension Committee of the Actuarial Standards Board determined that the inclusion of some educational material regarding arithmetic and geometric returns in ASOP No. 27 would be beneficial. The following material is not meant to be an exhaustive discussion of the matter. It is meant to give the actuary some direction regarding the considerations that may be employed in determining whether the use of arithmetic or geometric returns is more appropriate in the selection of a discount rate. In many circumstances, as with the selection of other assumptions, the purpose of the measurement is one of the most important determinants.

The use of a forward looking expected geometric return as a discount rate will produce a present value that generally converges to the median present value as the time horizon lengthens (i.e., if the actuary determines a funding obligation using the forward looking expected geometric return to discount the obligation to produce a present value, it is expected that in the limiting case there will be enough money to fund the obligation 50% of the time). The use of a forward looking expected arithmetic return as a discount rate will generally produce a mean present value (i.e., there will be no expected actuarial gains and/or losses).

This appendix should not be construed as a preference for any particular present value measurements over others (for example, market-consistent present value measurements or measurements using a discount rate reflecting anticipated investment return).

B. LOOKING BACK VERSUS LOOKING FORWARD

The discount rate used in the measurement of a pension obligation is a forward-looking assumption. While the actuary may use some historical results in establishing expectations regarding the future, the discount rate reflects an expectation of events to come, not events that have already occurred.

One of the more confusing aspects of the debate regarding arithmetic and geometric returns is as follows:

(a) determining whether we are talking about using historical results to establish forward looking (i.e., future) expectations, or

(b) determining whether we are talking about whether a forward looking expected geometric return or forward looking expected arithmetic return is a more appropriate discount rate

Note that a forward looking expected geometric return is not synonymous with compounding. That is, both a forward looking expected geometric return and a forward looking expected arithmetic return would be used in a compounding nature.

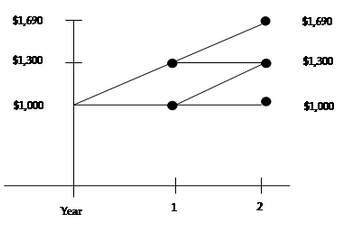

C. AN EXAMPLE

The following example illustrates the use of a forward looking expected arithmetic return to produce a mean present value. Assume that an asset class is expected to have a 50% probability of earning a return of 30% and a 50% probability of earning a return of 0% for each of the next two years and that these returns are the only possible outcomes. (The forward looking expected arithmetic return in this example would be 15%.) The chart below illustrates the totality of possible investment results for an initial $1,000 investment placed in this asset class:

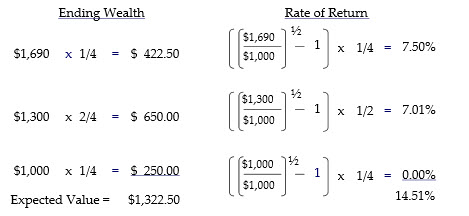

The expected ending wealth values and a derivation of the forward looking expected geometric return is presented below:

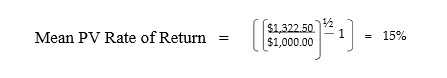

The forward looking expected geometric return in this example is 14.51%. The question then becomes what discount rate would take the expected value of $1,322.50 at the end of year 2 and produce a present value of $1,000? The answer is shown below:

which is the forward looking expected arithmetic return. Note however in this simple example, that if the actuary funded an obligation that is expected to be $1,322.50 at the end of year two with a one-time payment of $1,000 at the beginning of year 1, there would be insufficient funds at the end of year 2 three-quarters of the time.

D. CAPITAL MARKET ASSUMPTIONS FROM EXTERNAL SOURCES

In many instances, the actuary will collect capital market assumptions from external sources in order to determine the forward looking expected arithmetic return and/or the forward looking expected geometric return. The capital market assumptions can be broadly classified into the following categories:

(a) expected returns by asset class;

(b) standard deviations by asset class; and

(c) correlation coefficients between asset classes.

With respect to expected returns by asset class, some external sources report forward looking expected arithmetic returns, some report forward looking expected geometric returns and some report both. It is important to understand what type of return was collected as well as the future time horizon to which the expected returns apply.

In general, a forward looking expected geometric return for an asset class can be approximated by taking the forward looking expected arithmetic return and subtracting one-half of the variance of the asset class[1].

If the actuary is trying to determine the forward looking expected arithmetic return for an entire portfolio from individual asset classes, this can be accomplished by taking the appropriate weightings from the individual asset classes’ forward looking expected arithmetic returns. However, if the actuary is trying to determine the forward looking expected geometric return for an entire portfolio from individual asset classes, this cannot be accomplished by taking the appropriate weightings from the individual asset classes’ forward looking expected geometric returns. In approximating the forward looking expected geometric return for the entire portfolio, the actuary would first determine the forward looking expected arithmetic return for the entire portfolio and then subtract one-half of the variance of the entire portfolio.

Appendix 4 – Selected References for Economic Data and Analyses

The following list of references is a representative sample of available sources. It is not intended to be an exhaustive list.

- General Comprehensive Sources

a. Kellison, Stephen G. The Theory of Interest. 3rd ed. Colorado Springs, CO: McGraw-Hill, 2008.

b. Statistics for Employee Benefits Actuaries. Committee on Retirement Systems Practice Education, and the Pension and Health Sections, Society of Actuaries. Updated annually.

c. Stocks, Bonds, Bills, and Inflation (SBBI). Chicago, IL: Ibbotson Associates. Annual Yearbook, market results 1926 through previous year.

- Recent Data, Various Indexes, and Some Historical Data

a. Barron’s National Business and Financial Weekly. Dow Jones and Co., Inc. Available on newsstands and by subscription.

b. U.S. Bureau of the Census. Statistical Abstract of the United States. http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/

c. U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer Price Index. http://www.bls.gov/cpi/

d. U.S. Federal Reserve Weekly Statistical Release H.15. Interest rate information for selected Treasury securities. http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h15/

e. U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on Ways and Means. Green Book: Background Material and Data on Programs within the Jurisdiction of the Committee http://greenbook.waysandmeans.house.gov/

f. U.S. Social Security Administration. Social Security Bulletin. http://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/ssb/

g. The Wall Street Journal. Daily periodical. Available on newsstands and by subscription.

- Forecasts

a. Blue Chip Financial Forecasts. Capital Publications, Inc., P.O. Box 1453, Alexandria, VA 22313-2053. March and October issues contain long-range forecasts for interest rates and inflation.

b. Congressional Budget Office’s economic forecast. The forecast projects three-month Treasury Bill rates, 10-year Treasury Note rates, CPI-U, gross domestic product, and unemployment rates. http://www.cbo.gov/publication/43907

PDF Version: Download Here

Last Revised: September 2013

Effective Date: September 30, 2014

Document Number: 172

Document Status: superseded