Actuarial Standard of Practice No. 45

The Use of Health Status Based Risk Adjustment Methodologies

STANDARD OF PRACTICE

TRANSMITTAL MEMORANDUM

January 2012

TO: Members of Actuarial Organizations Governed by the Standards of Practice of the Actuarial Standards Board and Other Persons Interested in the Use of Health Status Based Risk Adjustment Methodologies

FROM: Actuarial Standards Board (ASB)

SUBJ: Actuarial Standard of Practice (ASOP) No. 45

This document contains the final version of ASOP No. 45, The Use of Health Status Based Risk Adjustment Methodologies.

Background

Health status based risk adjustment methodologies have been an important tool in the health insurance marketplace since the 1970s. The use of risk adjustment has significant effects on health insurance companies, healthcare providers, consumers, employers and others. The importance and influence of health status based risk adjustment methodologies are likely to increase as healthcare programs that currently use risk adjustment expand the populations they cover and other programs adopt the use of risk adjustment. ASOP No. 12, Risk Classification (for All Practice Areas), provides guidance to “all actuaries when performing professional services with respect to designing, reviewing, or changing risk classification systems used in connection with financial or personal security systems.” It applies more broadly than this ASOP. This ASOP is intended to provide guidance regarding the appropriate use of health status based risk adjustment models and methods. This standard requires actuaries to explicitly consider important characteristics of the risk adjustment models and their use, rather than allowing actuaries to assume important issues are already addressed within any given risk adjustment software model.

Exposure Draft

The exposure draft of this ASOP was approved for exposure in April 2011 with a comment deadline of July 31, 2011. Ten comment letters were received and considered in developing modifications that were reflected in the final ASOP. For a summary of the issues contained in these comment letters, please see Appendix 2.

Key Changes

The most significant changes from the exposure draft were as follows:

1. A definition for estimation period was added to the definitions section, the term “data collection period” was changed to “incurral period” in section 3.1.5 and further background on timing issues was added to Appendix 1.

2. In Section 3.1.3, language was added to address instances where descriptions of changes from a prior model version were not available.

3. Section 3.2, Input Data, was rewritten to clarify the meaning.

4. In section 3.6, the level of transparency afforded by the model was added as a consideration in recalibration of the model.

The ASB thanks everyone who took the time to contribute comments and suggestions on the exposure draft.

The ASB voted in January 2012 to adopt this standard.

Health Risk Adjustment Task Force

Ross A. Winkelman, Chairperson

Robert G. Cosway Kevin C. McAllister

Ian G. Duncan Julie A. Peper

Vincent M. Kane William M. Pollock

John C. Lloyd

Health Committee of the ASB

Robert G. Cosway, Chairperson

David Axene Nancy F. Nelson

John C. Lloyd Donna Novak

Cynthia Miller Ross A. Winkelman

Actuarial Standards Board

Robert G. Meilander, Chairperson

Albert J. Beer Thomas D. Levy

Alan D. Ford Patricia E. Matson

Patrick J. Grannan James J. Murphy

Stephen G. Kellison James F. Verlautz

The ASB establishes and improves standards of actuarial practice. These ASOPs identify what the actuary should consider, document, and disclose when performing an actuarial assignment. The ASB’s goal is to set standards for appropriate practice for the U.S.

Section 1. Purpose, Scope, Cross References, and Effective Date

1.1 Purpose

This actuarial standard of practice (ASOP) provides guidance to actuaries applying health status based risk adjustment methodologies to quantify differences in relative healthcare resource use due to differences in health status.

1.2 Scope

This standard applies to actuaries quantifying differences in morbidity across organizations, populations, programs and time periods using commercial, publicly available or other health status based risk adjustment models or software products. It does not apply to actuaries designing health status based risk adjustment models. Actuaries who perform professional services with respect to designing, reviewing, or changing risk classification systems should be guided by ASOP No. 12, Risk Classification (for all Practice Areas).

If the actuary departs from the guidance set forth in this standard in order to comply with applicable law (statutes, regulations, and other legally binding authority) or for any other reason the actuary deems appropriate, the actuary should refer to Section 4.

1.3 Cross References

When this standard refers to the provisions of other documents, the reference includes the referenced documents as they may be amended or restated in the future, and any successor to them, by whatever name called. If any amended or restated document differs materially from the originally referenced document, the actuary should consider the guidance in this standard to the extent it is applicable and appropriate.

1.4 Effective Date

This standard is effective for any professional services using health status based risk adjustment methodologies performed on or after July 1, 2012.

Section 2. Definitions

2.1 Carve-out

A medical service or condition not covered by the program under review or covered under a different reimbursement arrangement, such as a capitation. A common carve-out is mental health services.

2.2 Coding

The process of recording and submitting information (for example, diagnoses or services provided) on claims forms.

2.3 Condition Category

A grouping of medical conditions that have similar expected healthcare resource use or clinical characteristics.

2.4 Credibility

A measure of the predictive value in a given application that the actuary attaches to a particular body of data (predictive is used here in the statistical sense and not in the sense of predicting the future).

2.5 Diagnostic Services

Services (for example, lab or radiology) provided to determine whether a medical condition exists. Having these services performed does not by itself indicate a condition exists, although the result of the test may indicate it does.

2.6 Estimation Period

The period for which differences in morbidity are being quantified by the risk adjustment methodology.

2.7 Expert

One who is qualified by knowledge, skill, experience, training, or education to render an opinion concerning the matter at hand.

2.8 Health Status Based

Using healthcare claims, pharmacy claims, lab test results, health risk appraisal or other data based on underlying conditions or treatment as well as demographic information such as age and gender.

2.9 Morbidity

The incidence of or resource use associated with a medical condition or group of conditions.

2.10 Program

Health benefit programs including but not limited to commercial and employer sponsored health insurance, self-funded employer health insurance, and government sponsored health insurance, such as Medicaid and Medicare.

2.11 Recalibration

The process of modifying the risk adjustment model, usually the risk weights. Recalibration is often used to make the risk adjustment model more specific to the population, data, and other characteristics of the project for which it is being used.

2.12 Risk Adjustment

The process by which relative risk factors are assigned to individuals or groups based on expected resource use and by which those factors are taken into consideration and applied.

2.13 Risk Weight

The value assigned to each condition category that indicates the expected contribution of that condition category to an individual’s estimated resource use.

Section 3. Analysis of Issues and Recommended Practices

3.1 Model Selection and Implementation

The actuary should select an appropriate risk adjustment model and implementation methodology, based on the actuary’s professional judgment, with consideration given to the items discussed below.

3.1.1 Intended Use

The actuary should consider the degree to which the model was designed to estimate what the actuary is trying to measure. For example, the model may have been developed to estimate differences in total allowed costs, while the actuary may be trying to measure or project differences in paid costs for a high deductible plan, or differences in allowed costs for a single service category such as pharmacy.

3.1.2 Impact on Program

The actuary should consider whether the risk adjustment system may cause changes in behavior because of underlying incentives. For example, it may not be appropriate to include a health plan’s cost or provider’s prior charges as a risk adjustment variable when risk adjustment is used in determining health plan or provider payment.

3.1.3 Model Version

Since models are often updated, the actuary should consider the specific version of the model being utilized. If the actuary is using a new version of a previously utilized model, the actuary should consider the materiality of changes to the model. If a description of the changes from a prior version is not available, the actuary should consider comparing results under different model versions.

3.1.4 Population and Program

The actuary should consider if the population and program to which the model is being applied are reasonably consistent with those used to develop the model. For example, some models are intended for a commercial population and program while others are intended for Medicare or Medicaid. In addition, some Medicaid programs exclude carve-outs such as pharmacy and mental health services from the list of health plan at-risk services.

3.1.5 Timing of Data Collection, Measurement, and Estimation

Typically, at least small differences in timing between the development of the model and the application of the model will exist. The actuary should consider the impact of differences between the application of the model and its development with respect to timing issues such as the incurral period, estimation period, and claims run-out period.

3.1.6 Transparency

The actuary should consider the level of transparency that is appropriate for the intended use, and whether the model affords that level of transparency. For example, some commercially available models do not allow risk weights to be published.

3.1.7 Predictive Ability

The actuary should consider the predictive ability of the model and the characteristics of the various predictive performance measures commonly used and published.

3.1.8 Reliance on Experts

Risk adjustment models may incorporate specialized knowledge that may be outside of an actuary’s area of expertise. The actuary should consider whether the individual or individuals upon whom the actuary is relying are experts in risk adjustment and should understand the extent to which the model has been reviewed or opined on by experts in risk adjustment models.

3.1.9 Practical Considerations

The actuary should consider practical limitations and issues with any given model and methodology including the cost of the model, the actuary’s and other stakeholders’ familiarity with the model, and its availability.

3.2 Input Data

The type of input data that is used in the application of risk adjustment should be reasonably consistent with the type of data used to develop the model. Also the type of input data should be reasonably consistent across organizations, populations, and time periods. If such consistency is not possible, the actuary should document why the combination of that data and the selected model was used, and any adjustments made to the data, model, or methodology to address limitations in the data. If sufficient information concerning the quality and type of input data used to develop or apply the model is not available, the actuary should consider whether use of the model is appropriate. When evaluating consistency of input data, the actuary should consider the following:

3.2.1 Provider Contracts

The actuary should consider the differences in provider contracts and the potential impact of these differences on the risk adjustment results. For example, one organization may pay fee for service and another may pay capitation. This can cause significant differences in risk adjustment results based on data quality rather than morbidity.

3.2.2 Diagnostic Services

The actuary should determine how the model handles diagnostic services and whether data for those services should be included in the data input into the model.

3.2.3 Coding and Other Data Issues

Because risk adjustment model results are affected by the accuracy and completeness of diagnosis codes or services coded, the actuary should consider the impact of differences in the accuracy and completeness of coding across organizations and time periods. This standard does not require the actuary to quantify the portion of measured morbidity differences due to coding or other data issues and the portion due to true morbidity differences. However, the actuary should consider how coding, incomplete data, and other data issues may be affecting the results and consider whether adjustments to the risk adjustment process are appropriate. Adjustments may include phase-in, the use of alternate models, and adjustment for changes in coding over time or across organizations.

3.3 Program Specifics

The specifics of the program for which risk adjustment is being used should be considered. For example, the presence of reinsurance may affect the impact of high cost individuals or the program may carve out some services from costs that are at risk to health plans or providers.

3.4 Assigning Risk Scores to Individuals with Limited Data

The actuary should consider the minimum criteria required for an individual to be included in the risk adjustment analysis such as a minimum number of months of eligibility in the incurral period. Where these minimum criteria are not met, the actuary should identify an appropriate measure of morbidity to be used. Approaches to handling these individuals include, but are not limited to, assigning an age/gender factor, assigning an average risk score for the scored individuals or excluding them from the analysis while also dampening the results.

3.5 Addressing Model and Methodology Limitations

When implementing risk adjustment results, the actuary should consider any limitations with the data, model or underlying program fundamentals. The actuary may determine that risk adjustment results should be modified before application due to such limitations.

If using a risk adjustment model on a population for which it was not originally designed, the actuary should consider appropriate adjustments, such as recalibration and condition or demographic category groupings.

3.6 Recalibration

The actuary should consider the necessity and advantages of recalibration in the context of available resources, materiality of expected changes in results, appropriateness of the unadjusted model risk weights, level of transparency afforded by the model, and limitations in the data available for recalibration.

The actuary should consider the credibility of data and observations for specific condition categories before changes to the model are made. The actuary should consider the reasonability and implications of any changes to the relative weights for condition or other groupings.

3.7 Use in Combination with Other Rating Variables

When risk adjustment is used in combination with other rating variables such as age or gender, industry or area, the actuary should consider whether those variables capture differences in morbidity already captured by the risk adjustment model, and make the appropriate modifications.

3.8 Budget or Cost Neutrality

One of the goals of the risk adjustment application may be to shift funds without increasing or decreasing the overall budget or cost. In this situation, the actuary should consider changes in the composition of the group being risk-adjusted between the historic and projected time periods, changes in data coding and quality, program changes, and any other changes that have the potential to materially affect overall results.

Section 4. Communications and Disclosures:

4.1 Actuarial Communications

When issuing actuarial communications under this standard, the actuary should refer to ASOP No. 41, Actuarial Communications.

4.2 Disclosures

The actuary should include the following, as applicable, in an actuarial communication:

a. the disclosure in ASOP No. 41, section 4.2, if any material assumption or method was prescribed by applicable law (statutes, regulations, and other legally binding authority);

b. the disclosure in ASOP No. 41, section 4.3., if the actuary states reliance on other sources and thereby disclaims responsibility for any material assumption or method selected by a party other than the actuary; and

c. the disclosure in ASOP No. 41, section 4.4, if, in the actuary’s professional judgment, the actuary has otherwise deviated materially from the guidance of this ASOP.

Appendix 1 — Background and Current Practices

Health status based risk adjustment methodologies have been an important tool in the health insurance marketplace since the 1970s. The use of risk adjustment has significant effects on health insurance companies, healthcare providers, consumers, employers and others. Its importance and influence are likely to increase as healthcare programs that currently use risk adjustment expand the populations they cover and other programs adopt the use of risk adjustment.

Risk-adjustment is a powerful tool in the health insurance marketplace. Risk adjusters allow health insurance programs to measure the morbidity of the members within different groups and pay participating health plans fairly. In turn, health plans can better protect themselves against adverse selection and are arguably more likely to remain in the marketplace. This in turn increases competition and choice for consumers.

Risk adjusters also provide a useful tool for health plan underwriting and rating. They allow health plans to more accurately estimate future costs for the members and groups they currently insure.

Finally, risk adjusters provide a ready, uniform tool for grouping people within clinically meaningful categories. This categorization allows for better trend measurement, care management and outcomes measurement. The risk adjustment structure, like benchmarks for service category utilization, creates consistency in reporting and communication across different departments within an insurance company. For example, medical management, actuarial and finance professionals can measure the impacts of their care management programs.

Risk adjustment is widely used in government programs including Medicare Advantage, state Medicaid, and healthcare reform programs. In addition, it is used in provider payment, medical management, employer multi-option contribution setting and in many other applications that require objective estimation of morbidity.

Actuaries typically use models developed by commercial vendors or publicly available models such as CDPS, MedicaidRx or CMS’ HCC models. Concurrent models are usually used to measure morbidity when the incurral and measurement periods are the same, while prospective models are usually used if the estimation period is after the incurral period.

Concurrent models are used to analyze historical costs. Concurrent models can be used to assess relative resource use and to determine compensation to providers for services rendered because it normalizes costs across members with different health statuses. Normally, concurrent models provide an assessment of what costs should have been for members, given the conditions with which they presented in the past year. Prospective models are used to estimate future costs for a group of members.

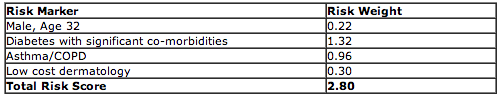

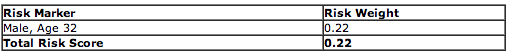

The following are examples of risk assessment (evaluation of risk at the individual or population level, resulting in risk scores) and risk adjustment (the use of risk scores to allocate reimbursement or assign costs among different individuals or populations). The risk assessment examples (Examples 1 and 2) below are taken from the American Academy of Actuaries’ May 2010 Issue Brief, titled “Risk Assessment and Risk Adjustment.” These examples show how the risk score for two different 32 year old males is developed based on their health claims history. (This is illustrative; not all risk adjustment models use this type of additive convention.)

Example 1: John Smith, age 32, has diabetes, asthma/COPD and dermatology diagnoses in his claims history.

The “Total Risk Score” in the table above is equal to the sum of the demographic and condition risk weights shown in the table. Usually, risk scores are stated relative to 1.0, with 1.0 being equal to the average expected risk score across the entire population. In this example, John Smith would be expected to cost 2.8 times an average member.

Example 2: Mark Johnson, age 32, has eligibility history but no claims.

In this example, the total risk score is equal to only the demographic risk weight and is much lower than the total risk score for John Smith. The estimated cost ratio using risk adjustment factors would be 0.22 / 2.80 or 0.079. Therefore, Mark Johnson’s costs would be expected to be 7.9% of those of John Smith, and 22% of those of an average member.

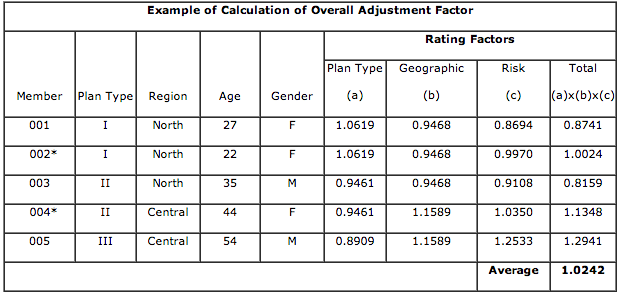

Risk scores can be aggregated for groups of individuals. The following example shows the application of relative risk scores within the risk adjustment process for the Massachusetts Health Insurance Connector (Exchange). This example is taken from Ian Duncan: Healthcare Risk Adjustment and Predictive Modeling (Actex Publications, 2011). In this example, the claim cost portion of the capitation rate was $393.67 per member per month (PMPM) at a 1.0 average plan type factor, 1.0 average geographic factor, and 1.0 average risk factor.

*Members 002 and 004 had seven or more months of experience during the historic experience period. Therefore, they receive a condition-based risk factor rather than an age/gender risk factor.

The relative risk factor, adjusted for geographic and plan type risk, is applied to the baseline risk premium and an administrative load ($32.00) is added:

$393.67X1.0242+$32.00=$435.20

This Health Plan would be paid $435.20 PMPM.

Appendix 2 – Comments on the Exposure Draft and Responses

The exposure draft of this ASOP, The Use of Health Status Based Risk Adjustment Methodologies, was issued in April 2011 with a comment deadline of July 31, 2011. Ten comment letters were received, some of which were submitted on behalf of multiple commentators, such as by firms or committees. For purposes of this appendix, the term “commentator” may refer to more than one person associated with a particular comment letter. The Health Risk Adjustment Task Force of the Health Committee of the Actuarial Standards Board carefully considered all comments received, and the Health Committee and ASB reviewed (and modified, where appropriate) the changes proposed by the Task Force.

Click here to view Appendix 2 in its entirety.

PDF Version: Download Here

Last Revised: January 2012

Effective Date: July 01, 2012

Document Number: 164

Document Status: Adopted